Borneo - A Lifetime Adventure

“Where are you from?” It seemed such a straightforward question when Coby asked me, and she was not the first.

I paused. “That rather depends what you mean.”

“Well, where were you born?”

“Ah. Borneo.” And now I have a twinkle in my eye, “I grew up in a tribe in the rainforest there. But then we moved back to Britain, first to Edinburgh in Scotland then to Winchester in England.”

Many people have heard of Borneo but will struggle to place it on a map, and for good reason. They get it confused with Burma, or just about anywhere else in the tropics, from Latin America to Africa or Asia. For a long time, Borneo was so remote and mysterious in people’s imagination it was synonymous with remote and mysterious, the home of the “wild man”, of headhunters and pirates.

Add to which, Borneo is not a country, but a huge island, the third largest in the world after Greenland and New Guinea, way bigger than France or Texas, which seem to have become international standard measurements. The larger part of Borneo belongs to Indonesia. The northwest quarter of the island principally belongs to the once-British Malaysian States of Sabah and Sarawak, which sandwiches the tiny, oil-rich Sultanate of Brunei.

I grew up in an isolated tribal community, the Sa’ban, in Sarawak. My parents were helping the local church translate the Bible into languages which had not yet even been written down in any form.

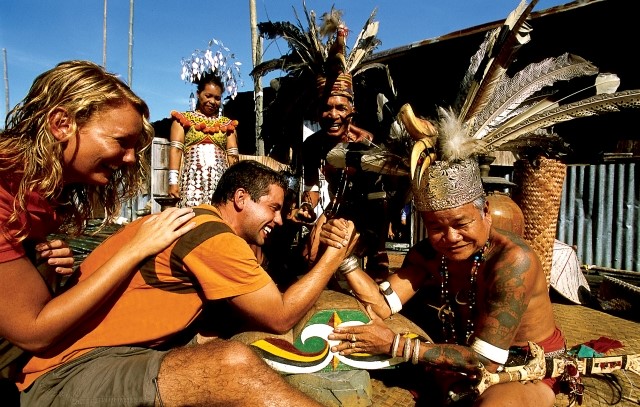

Plenty of locals in Borneo find my origins confusing too. “He is Sa’ban,” said my tribal brother, Ajang, recently, to a bewildered visiting agriculture department officer in Long Banga, our village. Certainly it is strange that I, a middle-aged white man, am accepted into the community and call the children in this photo “brother” and “sister” to this day. My association with Borneo goes way back. It is in my blood. And probably what led me to read Anthropology at Cambridge.

In the 1980s and 1990s Borneo was in the headlines for all the wrong reasons: its appalling rate of deforestation. Today the principle threat to orangutans remains loss of habitat to oil palm plantations. And for a number of years I campaigned vigorously on these issues. But over time I shifted my attention to small-scale, community-based eco-tourism projects. And there is hope.

I have brought The Young Presidents’ Organisation to Borneo; I helped organize an AGM for 264 top Unilever executives in Mulu National Park, to discuss the environmental and social impacts of their business; with Borneo Adventure and the Orangutan Foundation I helped inaugurate the Red Ape Trail in Ulu Ai: here, with local Iban tribes people who have long protected the orangutans, we managed to nudge the government to overturn timber and plantation licenses for the first time and to extend protected areas.

What is there to see?

Well, Borneo has some of the oldest rainforest in the world. It is home to an extraordinary array of species, including many not found elsewhere, like the orangutan, proboscis monkey or banded lemur. It has staggering scenery, from some of Jacques Cousteau’s favorite diving spots, to the highest mountain in South East Asia, Mount Kinabalu. And the forest is relatively benign. Friends doing research in Central America tell me horror stories about jiggers, snakes and disease, but, quite frankly, I feel as at home and almost as safe wandering beneath the towering trees of Mulu as I did strolling the beech woods near Oxford. Especially when there’s a Marriott Resort right in the middle of the jungle!

And of course, I love the people. I am not alone. Visitors come and are wowed by the wildlife along the Kinabatangan river, awed by the caves in Mulu, or coo at the quaint streets of Kuching, but time and time again I hear it is the friendliness of the people that touched their hearts and will bring them back again, and again.

Sarawak has a population a little over 2.5 million. There are more than 30 different ethnic languages spoken, alongside English and Malay. Borneans pride themselves on their diversity. Malays mix with Chinese and tribal peoples alike: when Muslims celebrate the end of the fasting month they throw “open houses” and everyone visits their Muslim friends to celebrate with them; when the Chinese celebrate their lunar new year, everyone visits their homes, and at Gawai, the tribal rice-harvest festival, the Chinese and Muslims visit their tribal neighbors for the festivities.

It should come as no surprise then that there is a fabulous choice of food on offer, from Malay to Indian or Chinese to tribal dishes, and fusions of these, as in the famous Laksa, a spicy coconut noodle soup so championed by Anthony Bourdain, or jungle ferns and chicken cooked in bamboo over an open fire. And of course western food is available everywhere too, often with local twists.

What is Borneo like?

Come and see for yourself. I have greatly enjoyed guiding ETV Endowment supporters around Europe in recent years, and we have had a lot of fun. We have become friends. From Downton Abbey days to funiculars up the Swiss Alps, we have watched Michelin-starred chefs cook us dinner in Brittany, danced a ceilidh in our own Scottish Castle and hunted truffles in Tuscany, but the trip I am most looking forward to is showing my ETV Endowment friends my Borneo.

Alasdair Clayre